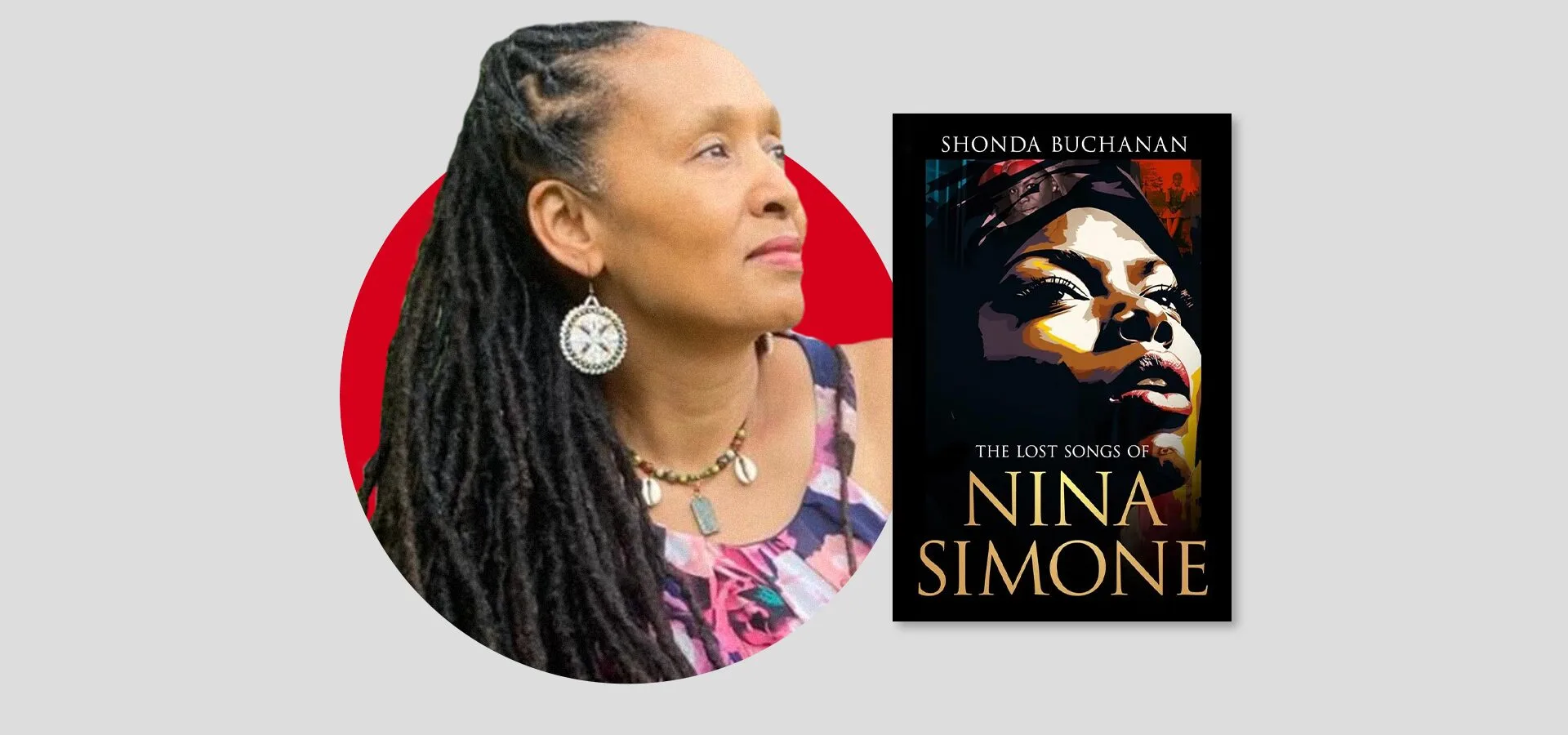

Shonda Buchanan | The PEN Ten

A poignant and intimate reflection on the life of one of the world’s foremost Black artists and activists, Shonda Buchanan’s newest collection The Lost Songs of Nina Simone (Rize, 2025) asks us what we recall of the prolific thinker. With decades of dedicated research, interview, and rumination, Buchanan presents an ode to strength, an ode to song, and an ode to revolution.

In conversation with former PEN America Los Angeles Programs and Operations Coordinator Ayana O’Brien for this week’s PEN Ten, Shonda Buchanan delves into her process for writing the collection, her experiences with her multi-hyphenate identity, and her dedication to supporting the careers of emerging writers. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

This collection is a powerful testament to the impact of Nina Simone’s life and legacy. How did you go about the process of researching for the collection?

This is such a great question because I think first and foremost, it was simply my adoration and appreciation for her music that led me to start writing poems about her. I gravitated towards her strength, her motherhood, her artistry. And then I started thinking about her life and where “Nina Simone” actually came from. That’s when I started researching her in earnest.

When I discovered that she was from North Carolina and her family were mixed race, that gave me such an epiphany in terms of how we never really know the strains of ethnicity in our blood until we actually have our own history or do the research. So I wanted to tell this story of this woman who impacted the world in such a significant way.

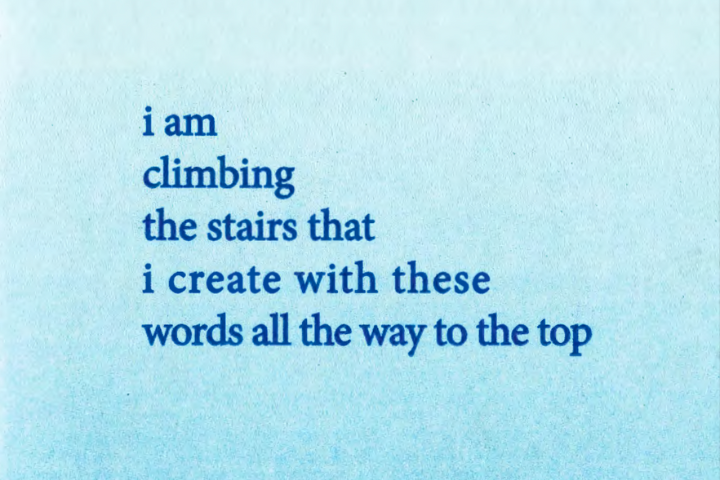

In the past you’ve written both poetry and nonfiction prose. What was your experience like making the decision to write this narrative in verse and then actually crafting it?

One of the things I really needed to pay attention to with this collection of poetry is how to capture her voice in persona poems. I wanted to make sure to represent her North Carolina upbringing and some of that country dialect that we could hear in her recordings. I definitely wanted to capture the essence of a young Black girl who was taught classical piano in the Jim Crow south. Which, in and of itself, was a kind of anomaly. I had to make those kinds of decisions about voice, tone, and word choice, making sure to represent the place where she came from and especially the people who surrounded her. And, of course, the evolution of her music.

I wanted to make sure to represent her North Carolina upbringing and some of that country dialect that we could hear in her recordings. I definitely wanted to capture the essence of a young Black girl who was taught classical piano in the Jim Crow south. Which, in and of itself, was a kind of anomaly.

The collection is structured into six sections, correlating around a theme of Nina Simone’s life. Most powerfully for me, each section also spans emotion—belonging, fear, pride, loss, returning. In what ways did you play with structure for the collection as a whole?

I knew I wanted to tell the story of her ancestors first because one of my fields of expertise is history, heritage, and inheritance. Her grandmother and great grandmother and great great grandmother, who were either enslaved Africans, full blood Indigenous natives, or Irish, all led to Eunice Waymon, aka Nina, being born. In both my African and Indigenous traditions, we always give thanks to the ancestors because we wouldn’t be here without them. I wanted to represent that aesthetic in the book.

Of course, all those childhood experiences that helped her understand what racism looks like and what being a daughter meant and the impact of music in the world, I needed to tell that story as well. Then, when she married her second husband who became her relentless manager, and also her abuser, I had to tell that story in the truest way I could.

Someone asked me if I interviewed Nina’s daughter for this book, and no, I didn’t. In fact, I didn’t even watch any of the movies about her while I was writing this book. I didn’t want to be influenced by anything or anyone else as I was crafting this book. I really wanted the artistry to arise from the images and the narrative.

The poems in the collection span voices and times—including family, audiences, and a few from the perspective of Nina Simone herself. How was your experience finding the voice you wanted for these poems?

There would be times when I wrote a poem, and I would just scratch out whole lines and stanzas because I felt like it didn’t represent her voice. I have to say while I knew she was my muse as I was writing this, I was also having dreams about her. In the dreams, she would be going through my house to see if I was good enough to write about her. That’s how deeply entrenched I was in this book project. How invested in trying to maintain her voice as an artist and also a world traveler. It’s impossible to capture everything about someone’s life, especially someone like Nina Simone, but I tried to the best of my ability.

One of the main themes of the collection is the idea of religion, both the complicated experience Black and Indigenous communities have had historically as a result of colonization, and the passion for it many people experience in their everyday lives. What was your process for placing and understanding religion in Nina Simone’s life?

Nina Simone was the daughter of a Mother Reverend who was strict on her, and a trickster father who made her laugh all the time. In fact, her father was a jack of all trades. But they were heavily entrenched in the church and gospel music. There’s a moment in Nina’s book when she talks about how her house was never quiet—how it was always full of music, either with singing or the piano, or some other instrument in the family.

When I finished one of the drafts of the book, I realized that I didn’t have poems about her as a child playing piano in church during some of those hot southern nights in North Carolina. So that’s where the two poems, “Watchnight I” and “Watchnight II,” came from, trying to capture the essence of Black folks who needed church and religion and faith to endure their lives in a racist state. Like her music and state of mind, Nina’s belief in religion flayed, faltered, maybe even disappeared at a certain time, but definitely plays a role in the poems.

Writing about Nina really made me see my own reflection in the mirror as a Black woman in America, as a mother, as an artist, as someone who has been married and divorced twice, and now is purposefully single because it seemed like my art always suffered when I was in a relationship. I understood so much of what Nina Simone went through in her career, in life, and motherhood.

A lot of Nina Simone’s life was about performance—performance in the literal sense as well as the performance that comes with her various roles and identities—Eunice, Nina, mother, singer, activist. What was your experience playing with this idea of performance in this collection?

I really wanted to embody a lot of her performance in many of these poems. Thinking about how she performed based off of what was going on in her life was definitely something I wanted to incorporate. I have a couple of poems in here that represent her going on stage to perform after she learned about the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and how she essentially broke down at that moment because the King was dead. Walking on stage that night was probably one of the hardest things she’d ever done, and after that she fell into a deep depression.

Your collection shows how important it is to understand Nina Simone in a kaleidoscopic manner, not just as hero or villain, but as a full person who lived with desires, trauma, joys, and inspirations. How did this experience writing about her shape your understanding of her as an artist? Yourself as an artist?

Writing about Nina really made me see my own reflection in the mirror as a Black woman in America, as a mother, as an artist, as someone who has been married and divorced twice, and now is purposefully single because it seemed like my art always suffered when I was in a relationship. I understood so much of what Nina Simone went through in her career, in life, and motherhood. This isn’t to say I regret becoming a mother or that I regret being in relationships, but I also see how I sacrificed a lot to be in those relationships with unsupportive men, and to work towards love, how I let my writing go. Luckily, my daughter was the one who really understood that I was a writer. I had very little difficulty being a mom even though motherhood is always time consuming. There would be so many times when I was writing, but I have to put down my pen and just cry.

The struggle for liberation that Nina Simone called for continues in our lives today. What hopes for a better future for those existing along the margins, informed by your exploration of Nina Simone, do you hope for the next generation?

I really think we need to teach Nina Simone—her music and her words—in our classrooms. Our students and this younger generation could learn so much about how to stand up and speak truth to power through art, and also how to self-care. What a powerful leader this person will be to know you have the opportunity to sacrifice for something that you believe in, while at the same time knowing when to take a deep breath, step back, and regroup so you can live to fight another day.

The one thing I think Nina Simone wasn’t allowed to do, something she ripped out of the air, was her right to rest when she went to Liberia. But in Liberia, even her freedom became a bit of an albatross for her because she was running away from something, hiding from things that she didn’t want to deal with.

I really think we need to teach Nina Simone—her music and her words—in our classrooms. Our students and this younger generation could learn so much about how to stand up and speak truth to power through art, and also how to self-care.

You’re involved with our Emerging Voices programming here at PEN America. These programs have been designed to uplift the careers of writers underrepresented in publishing. What speaks to you most about these programs and their mission?

Emerging Voices is such an important program for young and old writers who are trying to tell their stories. I was incredibly lucky to be in the program when I was younger, and I have always stayed close to PEN because something in me knew I needed to be close to this important community of writers. Particularly with the Freedom to Write project where they defend the rights of incarcerated writers who are labeled dissidents. I knew I wanted to be close to an organization that celebrated writers and also fought for us to the best of their ability. I am still friends with writers who I met in the Emerging Voices program 30 years ago. In my mind, that is the testament of the life of a real writer.

Other than Nina Simone, what other artists fuel or inspire you as a writer?

I grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and we were surrounded by Motown sounds, so all the music of The Temptations and Diana Ross, Tina Turner, Frankie Beverly, Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, and the Marvelettes inspired me and created my first sense of place and time. Yet, many writers who have inspired me—far too many to name in this article, but I will say all of the Harlem Renaissance writers, Toni Morrison, Sonia Sanchez, E.E. Cummings, Joy Harjo, Li-Young Lee, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Walter Mosley, Sharon Olds, Gloria Naylor, Edwidge Danticat, Lucille Clifton, and so many others. The list is endless.

Award-winning author and educator, Dr. Shonda Buchanan received her MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University. Author of the memoir, Black Indian, Shonda’s forthcoming books are The Lost Songs of Nina Simone and Children of the Mixed Blood Trail. For more information, visit www.shondabuchanan.com.