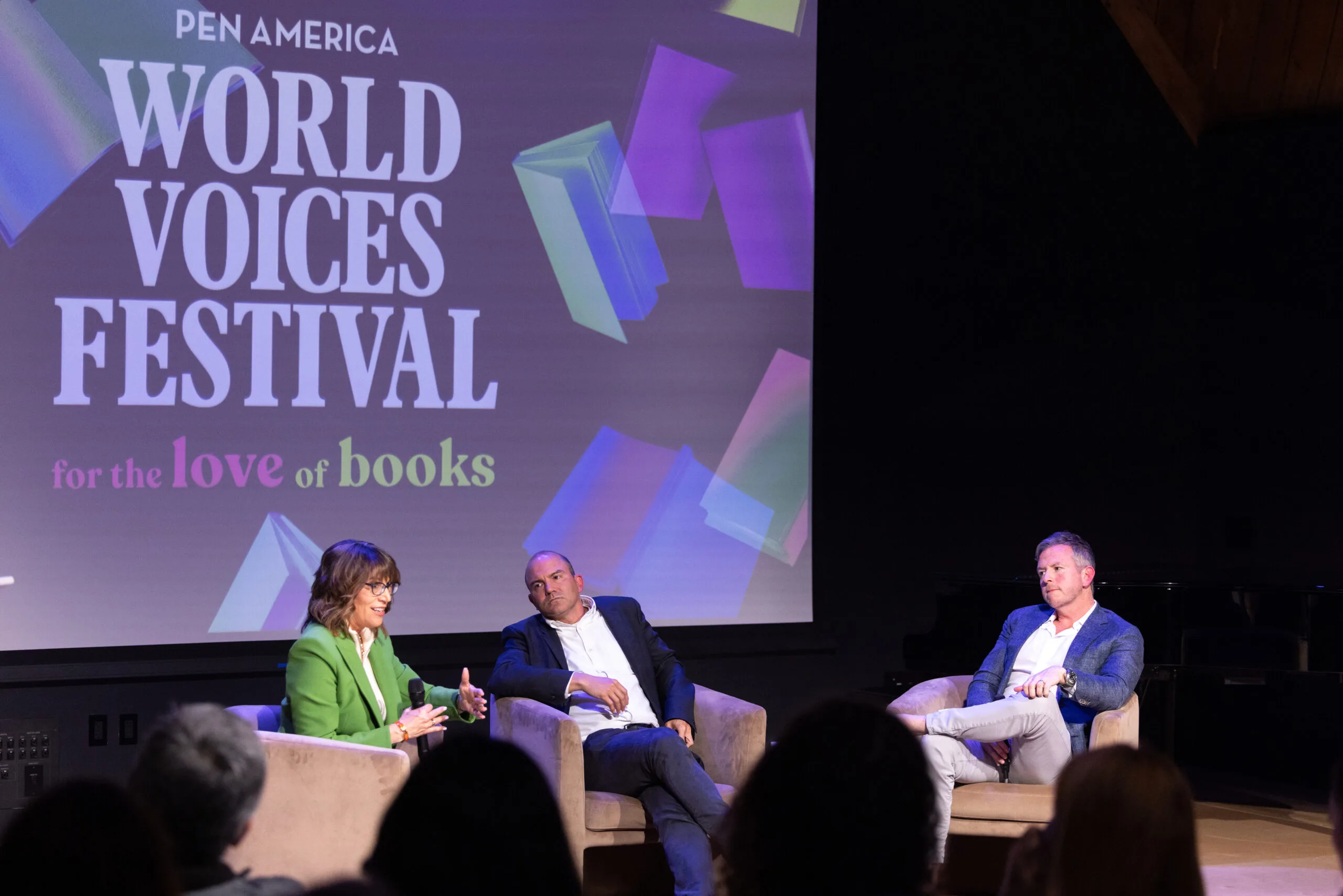

On May 2, 2025, the PEN World Voices Festival in Los Angeles hosted “Forced Journeys: Stories of Home, Displacement, and Belonging,” a luminous evening of storytelling, memory, and reflection held at the Goethe-Institut. Moderated by Turkish-American writer, activist, and scholar Ipek Burnett, the panel featured three acclaimed writers and artists: Charmaine Craig (Miss Burma), Lara Aburamadan (Refugee Eye), and Hector Tobar (Our Migrant Souls.)

Each brought a profoundly personal and political lens to the theme of displacement, drawing on their family histories, diasporic identities, and creative practices.

On the Meaning of Home

The conversation opened with a deceptively simple question: What is home?

Craig reflected on home as both a physical and emotional geography. She spoke of her mother’s exile from Burma and the way familial bonds shaped her identity growing up in Los Angeles. “We were all in liminal spaces together, but they were home,” she said.

Aburamadan, a Palestinian photo journalist from Gaza now living in Berkeley, described home as an emotional map made of memory and sense. “Home is where your loved ones are… You carry home with you,” she said.

For Tobar, home is both a gift and a paradox. As the child of Guatemalan exiles, he shared how Los Angeles became a meeting ground for diasporas, and how that multilingual, multicultural environment challenged U.S. ideas of identity. “Life is a journey,” he said. “That’s the lesson of exile.”

Home is where your loved ones are… You carry home with you

On Art, Identity, and Responsibility

Burnett asked the panelists how movement and creative work have shaped their sense of identity.

Craig spoke of writing her novel about the Keren people of Burma: “I had a lot of anxiety. Did I have permission to write this story?” Yet she came to see writing as a vow between artistic and ethical responsibilities. “It made me more secure about my hybridity.”

Aburamadan discussed her evolving identity as shaped by experience, ancestry, and survival. “Identity is the past, the present, and the future—in no set order,” she said. She described the painful aftermath of October 7 and the responsibility she feels to preserve and share images of a Gaza that no longer exist.

Tobar explored the immigrant storyteller’s role in fighting historical amnesia. “We’re told immigrants bring chaos, but in reality undocumented labor holds up this country,” he said. His creative work is driven by a need to expose those erasures. “To be an artist is to surprise people with truths they don’t see.”

To be an artist is to surprise people with truths they don’t see.

On Literature as Resistance

When asked whether fiction can be a form of resistance, the panelists offered moving affirmations.

Craig called literature a radical act of empathy: “In life, we can’t access another’s perspective fully. But literature lets us live inside another consciousness.”

Aburamadan emphasized art as a mode of truth-telling outside of institutional filters. “Art is where I can be honest. Activism can take many forms—sometimes just surviving is a form of resistance.”

Tobar reflected on entering the perspective of a perpetrator while writing The Tattooed Soldier. “To write the truth, I had to tap into my own shadow.” For him, literature’s strength lies in its refusal to simplify. “Boxes don’t fit us. The complications are what’s interesting.”

Want more? Check out the panelists’ books:

- Miss Burma by Charmaine Craig

- Refugee Eye by Lara Aburamadan

- Our Migrant Souls, The Tattooed Soldier by Héctor Tobar