The Blueprint State

Lessons from Parents Left Behind by “Parental Rights” Policies in Florida

PEN America Experts:

Director of Research & Insight, Florida Freedom to Read Project

Sy Syms Managing Director, U.S. Free Expression Programs

Senior Advisor, Freedom to Read

Director, PEN America Florida

Introduction

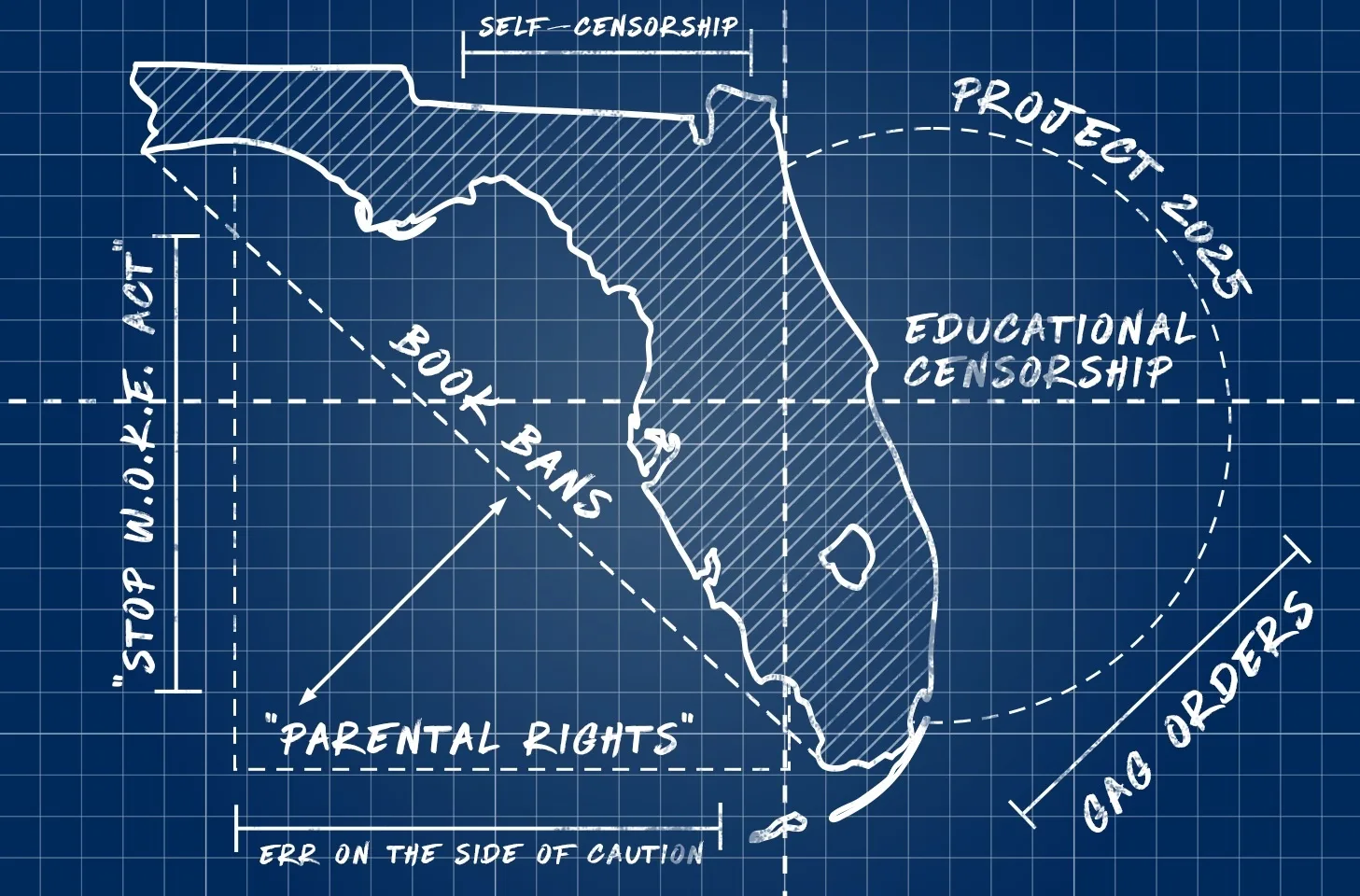

Since the start of 2025, free expression and freedom to read organizations have raised alarm over the new federal administration’s adoption of policies, practices, and rhetoric to suppress speech and restrict access to information. The administration has dismissed books bans as a “hoax,” chilled discussions of “race, color, sex, or national origin” by prohibiting so-called “discriminatory equity ideology” in K-12 schools, eliminated federal funding for promoting what it has termed “gender ideology,” and sought to advance ideological control of education under the guise of advancing “parental rights.”

Each of these federal actions has had a test run in Florida. Since 2021, the Sunshine State has led the country in advancing the “parental rights” agenda. Contrary to its name, this agenda has used fuzzy, coded language to manufacture moral panic, and to deliver control over what students can read and learn in schools not into the hands of all parents but to a particular segment of citizens — some not even parents but community members. The cumulative effect has been to privilege some parents’ ideological preferences above all others, tie the hands of educators, and limit students’ access to information through curricular prohibitions and book bans.

With the advent of the second Trump Administration, the country now faces the prospect that Florida’s approach to public education will become a blueprint for federal policy. For any informed national debate about these policies, it is imperative to examine the direct and indirect forms of censorship that these laws have enabled over the past four years: banning books about penguins and Michelangelo’s David, purging school and classroom libraries, canceling field trips and theatrical productions, censoring student clubs, and revising and removing certain textbooks. Though often trumpeted ardently by their supporters as advancing “parental rights”, this suite of education laws in Florida has had a detrimental impact on the state’s public schools, chilling the climate for teaching, learning, and open inquiry. Florida’s rising generation of students will bear the brunt of these short-sighted decisions.

In a report on “parental rights” legislation in 2023, PEN America cautioned that despite the fact that encouraging greater parental involvement in schools can seem like a “common sense” proposition, “these bills have an ulterior motive driving them: to empower a vocal and censorship-minded minority with greater opportunity to scrutinize public education and intimidate educators with threats of punishment.”

“After four years living under these laws as a Florida public school parent, nothing about “parental rights” policies are “common sense” in practice” said Florida Freedom to Read Project (FFTRP) co-founder, Stephana Ferrell. “Instead, it is a guise for a full throated censorship movement that serves to remake schools and especially the experience of our students, forfeiting their rights, as well as ours as parents. State officials are only interested in defending the rights of those that happen to agree with them.”

This brief provides key reflections and warnings based on this experience in Florida. Our goal is to offer others a deeper understanding of how various policies have played out on the ground, and to help those who want to fight this scourge and mount a strong defense of the right to read.

Reflections from the Ground

Reflection 1: “Parental Rights” Policies Subvert the Majority of Parents’ Preferences

Between 2021 and 2023, the DeSantis administration successfully pushed forward a “parental rights” package in Florida, through the passage of five state laws, numerous state policies, and various official communications. The laws include HB 241 (2021) “The Parents Bill of Rights”, HB 1557, HB 1467, and HB 7 (all passed in 2022), and HB 1069 (2023). Each of these laws was justified either explicitly or implicitly as part of the “parental rights” agenda.

Together, this suite of laws has led to astounding restrictions on topics such as race, discrimination, sexual orientation, and gender in schools. Despite the rhetoric of their supporters, “parental rights” – driven policies have subverted the majority of parents’ preferences, by making it easier for a single individual to chill classroom discussions and influence the availability of books for all. Supporters of “parental rights” claim to speak for the collective parent voice, yet data, included below, about Florida parents’ actual preferences proves otherwise.

One example of how these laws have had the opposite effect of what they claim is in the implementation of the 2023 law, HB 1069. The law mandates that books challenged for containing “sexual conduct” must be immediately removed from school libraries until they undergo a review process. In practice, this means that a single parent can challenge dozens of books and have them pulled from access for everyone else, without anyone confirming that the books meet the criteria for removal. The policy prioritizes the demands of those seeking to remove books over protecting students’ freedom to read, respecting the diverse preferences of all parents in the district, or honoring the professional judgment of librarians.

While Florida parents and guardians have been able to tailor their children’s access to library materials following best recommended practices by national professional organizations, HB 1069 formalized the process for a parent to set individual limitations for their children to access school libraries into law. Because of the way most districts implemented policies to comply with the law, we now have tangible data reflecting parental preferences on access to library materials.

In an analysis of public records collected by the Florida Freedom to Read Project from school districts, it is clear that the pathways for parental limitation fall into two basic camps. Some school districts allowed parents to opt-in, meaning the districts automatically limited students’ access to libraries until their parents approved it. For example, for the 2023-2024 school year, Clay County Schools required a permission slip signed by a parent for secondary level students (grades 7-12), to access the media center. Other districts allowed parents to opt-out, meaning the districts defaulted to full library access for all students until a parent requested limitations for their own children. Osceola School District and many others used this opt-out model, with parents capable of requesting additional levels of restrictions in their students’ library access.

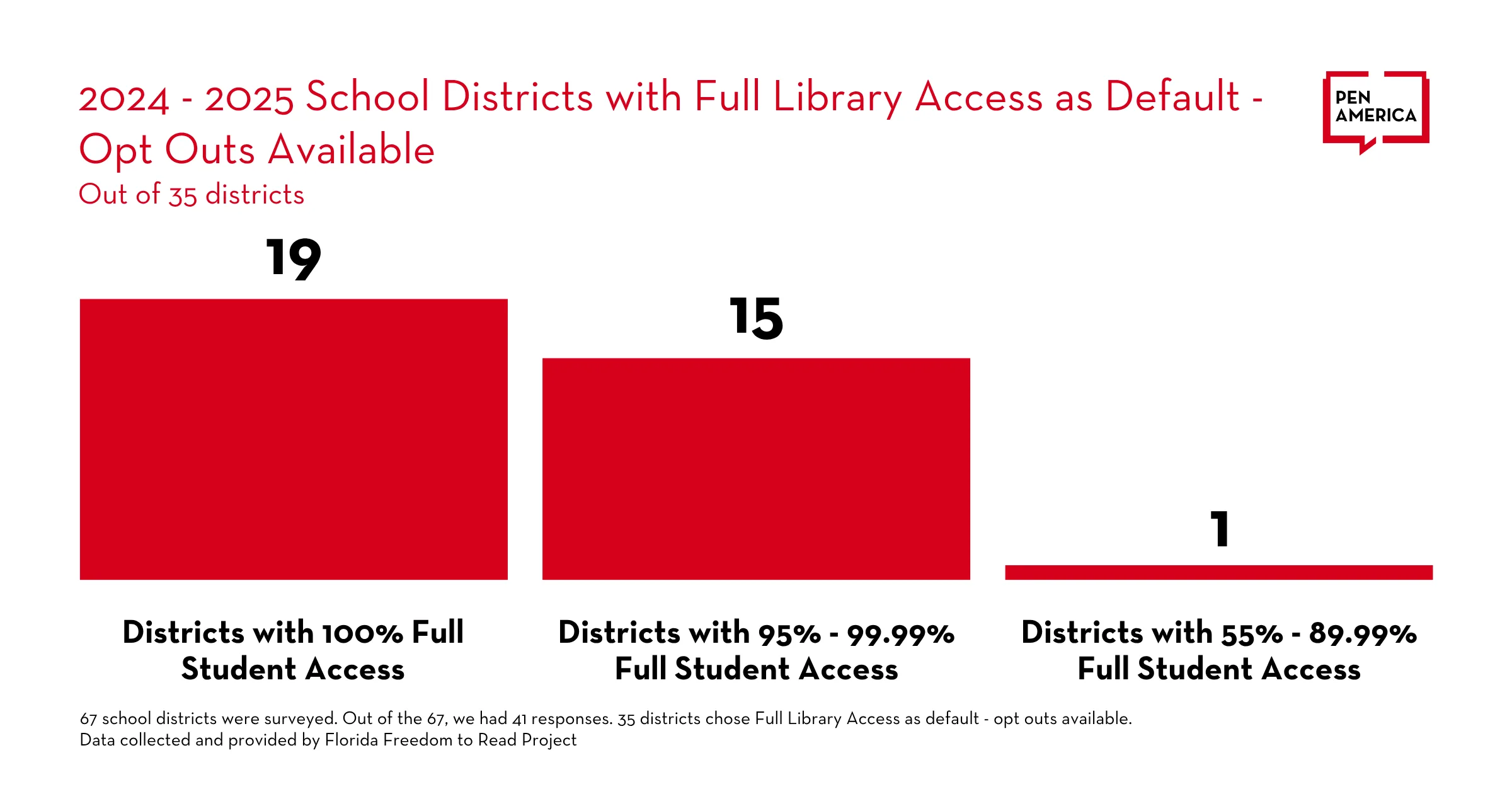

For the 2024-2025 school year, 41 of Florida’s 67 school districts responded to a public records request for information about library access policies. Among these 41 districts, the opt-out approach has been more popular, with 35 districts using opt-out, and 6 districts using opt-in. For those using opt-out policies, 19 of the 35 school districts reported that 100% of students maintained full library access. An additional 15 of these school districts reported that 95% – 99% of students maintained full access. Only one school district was slightly lower, reporting that 88% of students maintained full access.

In these districts, when given the opportunity to place library restrictions on their own students, the majority of parents overwhelmingly maintained full access instead.

For the same school year, 6 districts reported using opt-in policies. In these districts, there is variation in whether the default option if parents fail to turn in forms is no access for their students or restricted access. However, examining the forms that have been turned in reveals an overwhelming preference for full library access, once again. In 4 districts, over 90% of the forms submitted by parents opted for full access, and in the remaining 2 districts, over 80% did.

This data adds to the picture that the majority of Florida public school parents do not want their children’s library access in schools restricted. Because when given the choice, whether via opt-out or opt-in mechanisms, the majority of parents do not choose it. Overall, this signals trust in educators, libraries, and school library collections, and it runs counter to the notion of widespread fear and distrust espoused by “parental rights” supporters. Additionally, there are various recent polls and studies that affirm this finding.

Despite those clear preferences, the preferences of the majority of parents are being subverted by these laws and policies. As mentioned above, HB 1069 requires the immediate removal of a book challenged by an individual for “sexual conduct,” regardless of whether the objection can be substantiated. This means the majority of parents that expect their students to have full access to their school libraries can have their choices erased by a random objector. Florida parents are being subjected to a state law that prioritizes the removal of books before their informed review, and ignores their actual preferences altogether.

Reflection 2: “Parental Rights” Policies Lead School Districts to Self-Censor

During the 2023-2024 school year Seminole County Public Schools removed over 140 titles and placed restrictions on more than 30 other titles during the 2023-2024 school year. But, the choice to ban these titles were not triggered by any formal objection to them by local parents or citizens. Instead, the titles came from a different source: a list compiled by the state government of books removed in any Florida district during the previous school year.

This is one of the ways that laws in Florida have facilitated book banning on a wide scale. As part of HB 1467, passed in 2022, the Florida Department of Education was mandated to collect and report publicly on any book removals in any school district. As a result, district leaders face pressure to mimic one another’s library materials decisions, or, in other words, ban books in one district if they’re banned in others.

This is what happened in Seminole, where an “audit” of the library’s collection was driven in large part by the county’s local Moms for Liberty chapter, a special interest group that commonly advocates for increased “parental rights.” Through public comments at school board meetings, emails to board members, and a public campaign on social media, Moms for Liberty members pressured decision-makers within the district to review books removed in other districts in the state. If a title in Seminole’s collection matched a book on the state-compiled list, it subsequently faced removal or restriction.

This audit and subsequent removals happened despite the fact that at the start of the 2023-2024 school year, every student at Seminole County Public Schools had full access to the library (based on data collected by FFTRP). In this case, books were not challenged by any district parents and therefore not reviewed and considered in their entirety by a public committee review process. The overly broad audit thus ignored the preferences of Seminole parents who had not set library limits on their students’ access.

Furthermore, even if parents wanted to object to these state-list driven removals and restrictions, they could not. As affirmed by a federal judge, nothing in HB 1467 gives parents the ability to appeal the removal, restriction, or rejection of material they feel their child has an educational need for and a First Amendment right to access.

Seminole is not the only district to use the state’s lists to guide local curation, but up until recently the state has maintained that the lists are simply for reference, and do not obligate districts to conduct a review. However, in spring 2025, both the Education Commissioner and Florida Attorney General have written open letters to Hillsborough County Public Schools pressuring the district to utilize the list in a more active way. The district responded by pulling every title on the lists from student access (over 600 of them) until they can be reviewed for compliance with the current language in the law.

As seen in Seminole, HB 1467 has helped accelerate the ability of parents to ban books, even in districts where they do not have children in the schools, effectively catering to the minority of parents who want to censor them — wherever they are located — despite the majority of local parents who want to maintain broad access to literature for their students. It has also put pressure on district leaders to self-censor their library collections in advance of or in response to any challenges, no matter where they originate within the state.

Reflection 3: “Parental Rights” Policies Favor Censorship Advocates, Whether They’re Parents or Not

One of the recurring criticisms of those who espouse and utilize “parental rights” laws to restrict books in schools is that they often aren’t actually public school parents themselves. In numerous school districts in 2021-2023, some of the most prolific objectors to books would regularly discuss how they were pursuing a personal mission to rid school libraries of materials they deemed inappropriate, even though their own kids and families weren’t directly impacted by them.

Ostensibly to confront this issue, in 2024, the DeSantis administration pushed and passed HB 1285, to restrict county residents who are not parents of students with access to a public school library to filing only one objection per month.

But while this policy seemed to favor protecting the availability of books in schools to serve local parents, in practice it has done little to stop those who want to engage in serial book challenges.

In Santa Rosa County Schools, Florida, more than 50 books have been on hold for over a year, awaiting a committee review. Many of these objections come from a Florida resident living in a neighboring county, who has filed over 200 objections in her school district, Escambia County Public Schools. To bypass restrictions in HB 1285, this individual obtained power of attorney for some Santa Rosa residents, allowing her to submit objections on their behalf. This has allowed her the opportunity to challenge so many books en masse, even though she is not a local parent or resident, as the law requires.

When it comes to public input to school library materials or curricula, being a parent or not shouldn’t necessarily bar a resident in the district from making their opinion known to school district leaders at a school board meeting or through other channels. However, the Santa Rosa case illustrates how the systems for such public input can be easily abused. It also shows how the movement for “parental rights” is often used to cover obvious efforts at censorship since challenges like this don’t actually involve local parents’ concerns at all.

On the other side of the state, Nassau County School District faced a lawsuit in 2024 brought by the authors of And Tango Makes Three, Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, as well as students and parents in the district, after local organizers from another group, Citizens Defending Freedom, pressured the quiet removal of over 30 titles from their school libraries during the 2023-2024 school year. The school district and plaintiffs agreed to a settlement in September that was supposed to return most of the books to shelves and send a few back for a full committee review, allowing parents to opt their teens into having access while they await a final determination. A judge signed off on the agreement in November of last year.

Displeased with the settlement agreement, Citizens Defending Freedom launched a campaign to again pressure for the removal of books. In a press release, they called on Governor DeSantis to remove the voter-elected Superintendent and school board, and went to the Nassau Sheriff’s Office to complain about the books, alleging they violated obscenity laws. And when that didn’t work, public records documents reveal the group began to file formal objections to the titles, claiming they are “pornographic” and “harmful to minors.” This means that most of the books have been taken off the shelves once more for review, not available to students regardless of whether they have their parents’ permission, and again, at the request of very few. This happened despite 99.5% of students having full access to the library collection via the district’s opt-out policy, and the district’s promise to return the books as part of their lawsuit settlement.

Reflection 4: “Parental Rights” Policies Prioritize Caution Ahead of Students’ Education

In January 2023, the Florida Board of Education approved a required training and certification for librarians, media specialists, and others on how to select library and reading list materials. This was required as a provision of HB 1467 and was designed to facilitate local district compliance with it and with two additional “parental rights” bills, HB 7 and HB 1557, all of which went into effect on July 1, 2022. One element of the training quickly garnered attention across Florida. It was a slide that encouraged media specialists to “err on the side of caution while selecting materials” for their school library collections.

But, what does that mean? And what does it mean that the Principles of Professional Conduct for the Education Profession in Florida were subsequently updated to infer that an education professional’s certification could be at risk if someone suggests they have not used appropriate “caution”?

Across Florida, educators and principals were unsure, but they got the message that “err on the side of caution” means to “err on the side of censorship” and hoped their decisions concerning individual book titles wouldn’t result in a complaint that could end their careers. This in turn has created a system where the ideological preferences of the state have become the de facto opinions of educators. In other words, in practice, “parental rights” rhetoric has meant educators must practice extreme caution, catering to the most restrictively-minded. In turn, this means that actual parent input has been curtailed or completely cut out of the process of reviewing books their students can access in schools.

Manatee County is one great example. To protect their educators from uncertain consequences, in January 2023, school administrators ordered classroom libraries shuttered out of caution, following the guidance in state training, until a certified media specialist could review and approve each book contained therein. District and school leaders were concerned that these voluntary libraries, having never been curated by a certified media specialist before, might be out of compliance with the law and risk the educators’ certificates. After the library closures, local parents were rightfully upset, and the press took notice. The state’s response? Blame the teachers. They suggested some educators were using this opportunity to make a political statement and were purposely denying access to educational materials, despite the district memo that advised teachers to “remove or cover all materials that have not been vetted” for compliance with the new state guidance.

The state continued to say this every time another district made the news for covered shelves. And in May of 2024, it eventually led to the addition of guidance specifically directed at school principals in the “Principles of Professional Conduct” that administrators cannot allow educational materials to be withheld from student access unless they believe the material violates state statute. As a result, principals in Florida facing book challenges have been placed into an impossible bind, where the decision to retain or censor a book could result in a loss of certification for themselves or the educators they are charged to lead.

Yet, even after all this hoopla, Manatee is still struggling with precautionary censorship. The review process in Manatee allows principals, fearing they might be found in violation of vague state laws and rules that blur the lines between instructional materials and library books, to handle most objections without having to publicly disclose the objection, read the book in full, or form a review committee with parents or educators. No committee means no parental input in the challenge process. As a result, middle grade books intended for grades four through seven, like Drama by Raina Telgemeier, have been completely prohibited from their intended audience and limited to only high school readers. Other titles like The Freedom Writers Diary by Erin Gruwell have been declared “harmful to minors” and removed entirely from schools in the district.

Despite the rhetoric of favoring parental rights, in practice all of these decisions about book access are being made without any input whatsoever. No parents, no teachers or librarians, no transparency – No problem?

Reflection 5: “Parental Rights” Policies Codify the State’s Ideological Preferences

Before the passing of HB 1069 (2023), Orange County had annually approved a comprehensive sex education curriculum at the middle school level that included a range of topics, including consent, sexual violence, contraception, and prenatal development, in addition to an abstinence-focused message. This curriculum was available to all students at the appropriate grade level, with the option for a parent to opt them out.

Following the adoption of HB 1069, each district submitted their curriculum to the state Department of Education for approval. Orange County did so in the fall of 2023, anticipating gaining approval in time for a spring 2024 delivery. But the state failed to approve theirs or any other district’s submitted curriculum before June of 2024, so students in Orange County went without any formal instruction on puberty and sexual health during the entire 2023-24 school year.

After news broke that the state missed its deadline for the 2023-24 school year, it conducted a review for the 2024-25 curriculum, only to reject the comprehensive sex education program submitted by Orange County (and several other districts). The state apparently decided that certain topics were no longer age-appropriate and deviated from the “abstinence-only” health standard.

In reflecting on these developments, it’s important to remember that Orange County has a locally elected school board responsible to residents in that district, while the state Department of Education are employees responsible largely to the entire state and sometimes, as in the case of the Education Commissioner, state appointees. Nonetheless, once again the hand of the state is what dictated the local sex education curricula, with little consideration for local parents’ preferences.

Two other large school districts in the state, Broward and Palm Beach, are also struggling with delivering their intended curriculum during the current school year, facing similar issues with state approval. In the last few weeks of the school year, Broward announced that it will use the curriculum approved for use in Collier County over its own submission which was approved by the locally-elected Broward County School Board. In effect, regardless of what Broward parents voted for, they are being put in a bind to hew to a more restrictive-minded district’s preferences.

This insistence by the state to reject locally-approved curriculum diminishes the choices and voices of local parents and voters. In these districts, a parent’s ability to influence their children’s education has been diminished, as government entities are actually limiting it.

Conclusion: “Parental Rights” Policies put the state’s interests first, and all parents second

The inflammatory rhetoric around “DEI” and the call for “patriotic” education that have come from the current Trump administration might be new to some parts of the country, but Florida has been dealing with these ideas for years. When the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act” (HB 7) went into effect in July of 2022 for K-12 schools, it had much of the same language we see today in the “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling” executive order at the federal level.

So what does this look like in practice, according to the Florida government? And where do “parental rights” enter the picture?

See for yourself.

When Florida introduced specific African American history standards into the social studies curriculum in 2023, they did so with a whitewashed lens to avoid students having any feelings of “guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress,” as required by HB 7. Among the changes they made, the Florida Department of Education amended the standards to require instruction address “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit” and that when speaking about Black communities during Reconstruction and beyond, that “instruction includes acts of violence perpetrated against and by African Americans but is not limited to 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, 1919 Washington DC Race Riot, 1920 Ocoee Race Riot, 1921 Tulsa Massacre, and the 1923 Rosewood Massacre.” Additionally, topics that address racial oppression, racial segregation, and racial discrimination must be taught in an age-appropriate manner and free from “indoctrination.” None of these terms are clearly defined.

To put it plainly, the Florida government’s standards implied that American students should not have to feel “distress” when examining the country’s history of the enslavement of African Americans. These changes minimized African American history and culture, as well as the realities and legacy of enslavement, including by suggesting the experience of being enslaved was to these individuals’ ‘personal benefit.’ These changes also mandated teaching about violence perpetrated “by” African Americans, implying that the victims of racist violence invited it upon themselves.

People from all over the state, including those with diverse political views, united to demand the Commissioner take these standards back under consideration, given their obvious inaccuracies and bias. Additionally, there was ample evidence districts were already over-applying HB 7 using it to justify discriminatory censorship such as state rejection of submitted social studies textbooks, removing images of civil rights leaders from classroom displays, and withholding access to classroom library books that address such topics.

But, despite parents and educators speaking up, the Commissioner was propped up by HB 7 and able to ignore those calls.

In May 2024, the Social Studies standards were back before the state board. Parents and educators again voiced their concerns about the African American History standards. Instead of acknowledging the need to amend them, the Board declared that now was not the time for those adjustments. They were only concerned with approving the revisions to 9/11 History and Asian American/Pacific Islander History standards required by recent legislative changes. They also revised certain Civics standards to mandate the inclusion of the “Judeo-Christian” influences on our rule of law.

Standards matter. State standards dictate the information textbook publishers are required to provide if they want to earn state approval. It’s the framework educators must adhere to if they want to avoid the threat of de-certification. It’s the premise for all student discussions that are allowed to occur in the classroom when it comes to discussing the generational impacts of enslavement and white supremacist-driven massacres.

Although the teaching of African American History in Florida is meant to be free from indoctrination, two years after they were introduced, these flawed, inaccurate, and offensive standards are still in place. The experience of advocating to revisit the standards has made clear that in Florida, HB 7 has nothing to do with “parental rights”. Rather, it has been a tool to mute and remove many parents’ voices from influencing public education, and to create a public education system that serves the interests of the state first, and all parents, second.

Reclaiming Parental Voices for Education

No doubt, we will continue to see arguments made in court that libraries are “government speech” immune from any First Amendment challenge, that can be curated at the whims of elected officials (an issue at the heart of a recent federal appeals court decision about the removal of certain books from a public library in Texas). As there have been in many states, we can expect further calls for rating systems to be developed by special interest censorship groups to restrict what students can read and when. We can also expect more policies requiring libraries to create sections that discriminatorily segregate books, and laws allowing state governments to mandate what titles local districts cannot have or even criminalizing librarians and educators. And now that it’s caught on among state and federal policymakers alike, the threat of withholding public funding looms large as another tactic to force ideological control over access to information in our public institutions.

All of these trends in educational censorship build upon the tactics and precedent Florida’s government has set since 2021. Despite the political rhetoric, these laws are not popular, they are not the will of the people, and they are not what’s necessary to honor parents’ wishes.

As these threats move to the national arena, it is time for more parents to speak up and have their voices heard when it comes to public education.

Here are some ways to get or stay engaged:

- Find a local group that is showing up to protect the freedom to read in a way that connects with you. If there isn’t one, consider starting one. Fight for the First is a free platform developed by EveryLibrary for this reason.

- If you are an active member of a grassroots organization with an interest in first amendment issues, get connected to larger coalition efforts at the state or national level.

- Subscribe to Kelly Jensen’s weekly Literary Activism newsletter to stay in the know. She also has a much larger list than this one of simple things you can do to support the freedom to read.

- Reserve time on your calendar to regularly reach out to the elected officials that represent you, and ask for a virtual meeting when there is a policy or bill you’re concerned about.

- Make time to testify at public hearings, whether locally or in your state capitol.

- Host events that help bring local awareness to this issue and empower people to speak out in support of the freedom to read.

- Our favorite recommendation is a book exchange:

- The first 20-30 minutes are treated like a speed-dating event where attendees mingle and share what they loved about the book they brought to exchange for something new.

- The next 10-15 minutes discuss local, state, or national concerns around book bans and education censorship.

- The final 10-15 minutes are reserved for exchanging books and information to ensure people stay connected to your efforts.

- Our favorite recommendation is a book exchange:

- If you’re a writer (professional or hobbyist), consider submitting op-eds around this issue to your local paper, or authoring a petition or open letter that can be amplified by local, state, and national organizations or media.

- Connect with other parents at the Freedom to Read Project.

- Become a member of PEN America.

Florida is a warning sign of what this country could become when we allow a false narrative about “parental rights” to be used by the state to misrepresent the preferences of all parents. We should not let the Sunshine State become the blueprint for public education across the country.

Florida Freedom to Read Project

This report was co-written by the Florida Freedom to Read Project and PEN America. The Florida Freedom to Read Project is a volunteer effort led by two public school parents. It formed in 2022 out of necessity and in direct response to the impacts of Florida’s “parental rights” laws. As parents in the Sunshine State, these laws have infringed on our ability to direct the education and upbringing of our children.

As we considered a future where Florida’s blueprint is used at a national level to limit access in libraries and the classroom, we recognized a need for a parent-led organization that can support and uplift the work of everyday citizens like us. We are all too familiar with the bullying tactics used by censors that intentionally leave individual parents feeling alone, unsupported, and overwhelmed. We seek to inform, guide, and inspire parents and concerned citizens in their local communities – in both blue and red states – to feel empowered to speak up for the freedom to read and learn. That’s why we started the Freedom to Read Project.

PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect free expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible.

Since 2021, PEN America’s Freedom to Read Program has documented nearly 16,000 book bans in public schools nationwide. We have raised national awareness of a censorship campaign, organized by conservative groups, that predominantly targets books about race and racism by authors of color and also books on LGBTQ+ topics, as well as those for older readers that have sexual references or discuss sexual violence. We will continue to raise awareness and resistance to ongoing book bans to defend students’ freedom to read as we seek to ensure that all readers see themselves and the world around them reflected in the books shelved within their public schools and libraries.

| Law and Title | Key Provisions Impacting Access to Information |

|---|---|

| HB 241 (2021) “Parents’ Bill of Rights” | Prohibits the state, its political subdivisions, any other governmental entity, or other institution from infringing on a parent’s fundamental right to direct the upbringing, education, health care, and mental health of their minor child, except in narrow circumstances. |

| HB 7 (2022) “Individual Freedom Act” or “Stop W.O.K.E Act” (colloquial) | Prohibits public school educators from subjecting students or employees to training or instruction that “espouses, promotes, advances, inculcates, or compels” them to believe certain ideas about race, sex, color, or national origin. Classroom instruction related to past racial injustice may not “indoctrinate or persuade” students to believe these ideas. The law was challenged in 2022 and a preliminary injunction granted by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Florida has stopped HB 7 from being enforced in institutions of higher education. The preliminary injunction is on appeal in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. |

| HB 1557 (2022) “Parental Rights in Education Act” | Prohibits public K-12 schools from providing classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in grades K-3 or in grades 4-12 “in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” |

| HB 1467 (2022) | Requires school librarians and personnel involved in selecting school library materials to complete a state-developed training program on material selection to “assist reviewers in complying” with state laws. The subsequent training directed media specialists to “err on the side of caution while selecting materials” for their school library collections. ed media specialists to “err on the side of caution while selecting materials” for their school library collections. Public K-12 schools must report all materials that were objected to, and materials removed as a result of an objection, to the state Department of Education. |

| HB 1069 (2023) | Expands HB 1557 and HB 1467 to prohibit instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity through grade 8, requires health education to adhere to specified definitions of “sex,” and requires state approval for locally-selected reproductive health curriculum. School materials, including in a school or classroom library, may not “depict or describe sexual conduct” in an age-inappropriate way and any material objected to on that basis must be immediately removed until reviewed. An objector who is unsatisfied with the local school board’s decision may appeal to a state-appointed special magistrate and the State Board of Education. Appeal costs must be paid by the school district. |

| HB 1285 (2024) | Restricts county residents who are not parents of students with access to a public school library to filing only one objection per month. |

| FAR 6A-10.081 “Principles of Professional Conduct” (2022-2024) | These principles must be complied with in order to continue to remain eligible to be certified as an educator in the state of Florida. From 2022-2024, these principles have been updated numerous times to force compliance with new “parental rights” laws. These often include vague and broad language threatening educators’ certification, to intimidate educators into self-censorship. |

Learn More

-

The Blueprint State

A wave of education laws in Florida has had a detrimental impact on the state’s schools, chilling the climate for teaching and learning.

-

Treating Online Abuse Like Spam

Social media platforms are not sufficiently investing in mechanisms that alleviate the harms of online hate and harassment.

-

A Five-Alarm Fire for Free Speech

No federal administration has moved as swiftly to exert broad new controls over what people can say, read, learn, research, and think.

-

Freedom to Write Index 2024

The number of writers jailed reached a new high, with at least 375 behind bars in 40 countries during 2024, compared to 339 in 2023.

-

Exploring How to Build Community-Level Resilience Against Disinformation

Disinformation, and the ability to counter it, is intertwined with factors including trust, polarization, economic conflict, social isolation, prejudice, and mental health.

-

Cover to Cover

Introduction In the 2023-2024 school year, there were more than 10,000 instances of banned books in public schools, affecting more than 4,000 unique titles. These mass book bans were often the result of targeted campaigns to remove books with characters of color, LGBTQ+ identities, and sexual content from public school classrooms and libraries. As book…