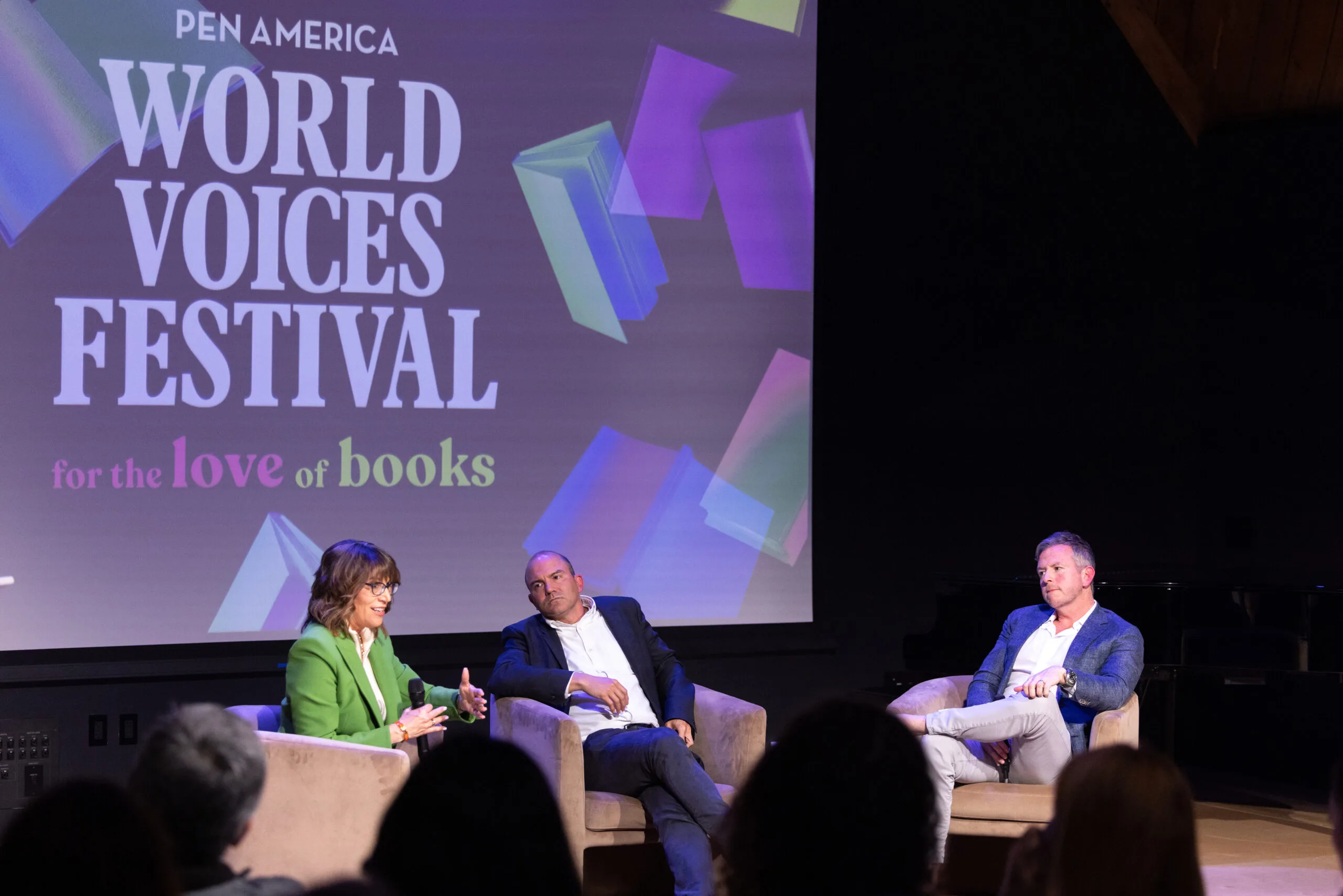

How do authors think about the publication of a new edition of their books written many years, even decades, earlier? At a PEN World Voices Festival conversation, two celebrated novelists, Joyce Carol Oates and Carmen Boullosa, talked about why and how reprints of books they wrote years, even decades ago resonate today. With more than 100 novels, nonfiction titles, plays, short story, and poetry collections published between them, these two prolific authors were uniquely suited to the evening’s discussion, “Bringing Back Books They Love.”

The conversation was moderated by Sabir Sultan, festival director and director of literary programs at PEN America, who asked each author to start off by reading a short passage from their reissued volumes— Oates’ from Broke Heart Blues, published in 1999 and reissued by Akashic Books last October, and Boullosa from Texas: The Great Theft, which Deep Vellum republished for its 10th anniversary last December. The reissued titles included new cover art and blurbs and for Broke Heart Blues, a self-reflective afterword by Oates and in the case of Texas: The Great Theft, a new introduction by noted literary critic Merve Emre.

Returning to a world of the past

The conversation turned to insights from the authors: Why did they revisit these titles now, have their views of the books changed from when they wrote them and, in a world that has changed significantly from when they wrote the books, are they still resonant and relevant?

Noted as a favorite among her 58 novels, Oates described Broke Heart Blues as a “tender and nostalgic” reflection on a particular world she inhabited as a teenager when she was bussed to Willliamsville South High School, in the upper middle class suburb outside of Buffalo, New York, from the working class farming community of Millersport, where she grew up, first in her family to graduate from high school. Willowsville, the fictional town she created as the setting for her book, is very close to the real Williamsville she remembers.

And yet even in this nostalgic look back more than 60 years, the novel presents an American archetype who might well spring from our own time. The book’s central character, John Reddy, is a quiet, enigmatic teenager when he is tried for killing his mother’s lover. Shelf Awareness described Reddy being turned into a “heartthrob of epic proportions” by the local high school’s “swooning girls and overeager boys” amid the trial’s media circus.

“This was a time in America before school shootings and cell phones,” said Oates. “People were more focused on their own locality [and] not looking too far beyond it. because they weren’t looking at their phones, like we do today. It was another era, which is such a contrast to our own… so electronically plugged in.”

But that is not the main theme of the book, which she described as “the romance of mythologizing people. I’m fascinated by mythologizing, the incessant need we have. We may be hardwired as humans to do this. We know life is very complex and we know no one person is perfect. But we do kind of revere the archetype.” Then as now, she said, a novel “is a snapshot in time.” But its larger themes certainly can be universal and lasting.

She said Broke Heart Blues at its core is “an investigation of how people are so very different” from how they present themselves. As she said, “the celebrity focus of American culture.” She also noted that while the novel has no politics at all in it, if she were writing it today: “I would add politics.”

I’m fascinated by mythologizing, the incessant need we have. We may be hardwired as humans to do this. We know life is very complex and we know no one person is perfect. But we do kind of revere the archetype.

Turning to Texas

Boullosa told the serendipitous story about how the 10th anniversary reissue of Texas: The Grand Theft came about.

She said a few years before the book was originally published in 2014, she was at a literary event and struck up a conversation with a young man. She told him the outlines of her work in progress, mentioning that she did not yet have a publisher. She said he told her: “‘I’m going to publish that book,’ though at the time he was not a publisher,” a line that drew laughter from the audience. Boullosa was impressed enough with the young man’s literary passion that she agreed to have him publish it on the spot. (She said her agent, when she relayed this story, said: “Are you nuts?” )

Fast forward to 2013 and the founding of Deep Vellum in Dallas by Will Evans, the young man Boullosa had met. The nonprofit independent publishing house he founded has since established a glowing reputation for publishing stellar and diverse literature in translation from around the world. Boullosa’s Texas: The Great Theft was the first book he published and so it was fitting that on its 10th anniversary, Deep Vellum would reissue the book.

The novel fictionalizes real events that took place in Brownsville, Texas, in the middle of the 19th century; the novel revolves around a white sheriff shooting a Mexican aristocrat. The central character and focus of the novel is Don Nepomuceno, a Mexican man who witnesses the sheriff mistreating a vaquero (cowboy), which becomes the trigger leading to his invasion of Texas to reclaim stolen Mexican land. Through the history of the Mexico-Texas border, the novel explores the complexities of colonization, land, violence, and the struggle for justice.

No one can overlook the relevance of the book to today’s crisis on the Tex-Mex border, and many reviewers have noted the important context the novel offers while also telling a gripping story.

Boullosa was born in Mexico and has taught writing at the City University of New York for many years; she has said bringing awareness to “the complexity of the inheritance of Texas” was her goal in documenting this history of the thefts and betrayals— some of it violently— of white people who stole land for themselves from Mexico.

In both cases, the authors were less explicit about the books’ relevance to the present, leaving it to the audience to decide for themselves whether the themes they heard described were indeed relevant. (Based on the line of attendees buying their books, the answer for many in the audience looked to be yes.)

Read the Books:

- Broke Heart Blues, by Joyce Carol Oates

- Texas, the Great Theft, by Carmen Boullosa